Sensemaking and Meaning Making in Informal Workplace Learning

Highlights

-

In many professions such as healthcare, there is a wealth of informal learning experiences at work. However, time pressures often prevent professionals reflecting on these experiences immediately.

-

Support is needed to recall these valuable experiences and elaborate on them individually or collaboratively in a useful way (i.e., make sense or meaning out of them).

-

We have developed a suite of tools that offer affordances to cope with each of those challenges in the problem or topic-focused sensemaking and meaning making of informal learning experiences.

-

Results of our studies show that the tools support recalling informal learning experiences in the form of “bits”, elaborating them by offering visual organization and sharing and collaborating on them in an asynchronous manner.

Prelude

The following sections are based on a 4 year long Design-Based Research (DBR) study. In this endeavour, research questions and hypotheses got re-defined and concretized several times as well as the respective study designs chosen to answer them appropriately. The resulting findings have been followed up, examined and reconfirmed in each of the design iterations to check their validity. Providing the chronological history of those research questions, hypotheses, study designs and findings is too substantial, which is why it will be reported in an aggregated manner reporting all of the challenges in one section as well as all the findings. To shed some light on the origins of those claims the iterations are stated in bold in brackets. Please, see Figure 3 to allocate the iterations alongside the phases of DBR [1].

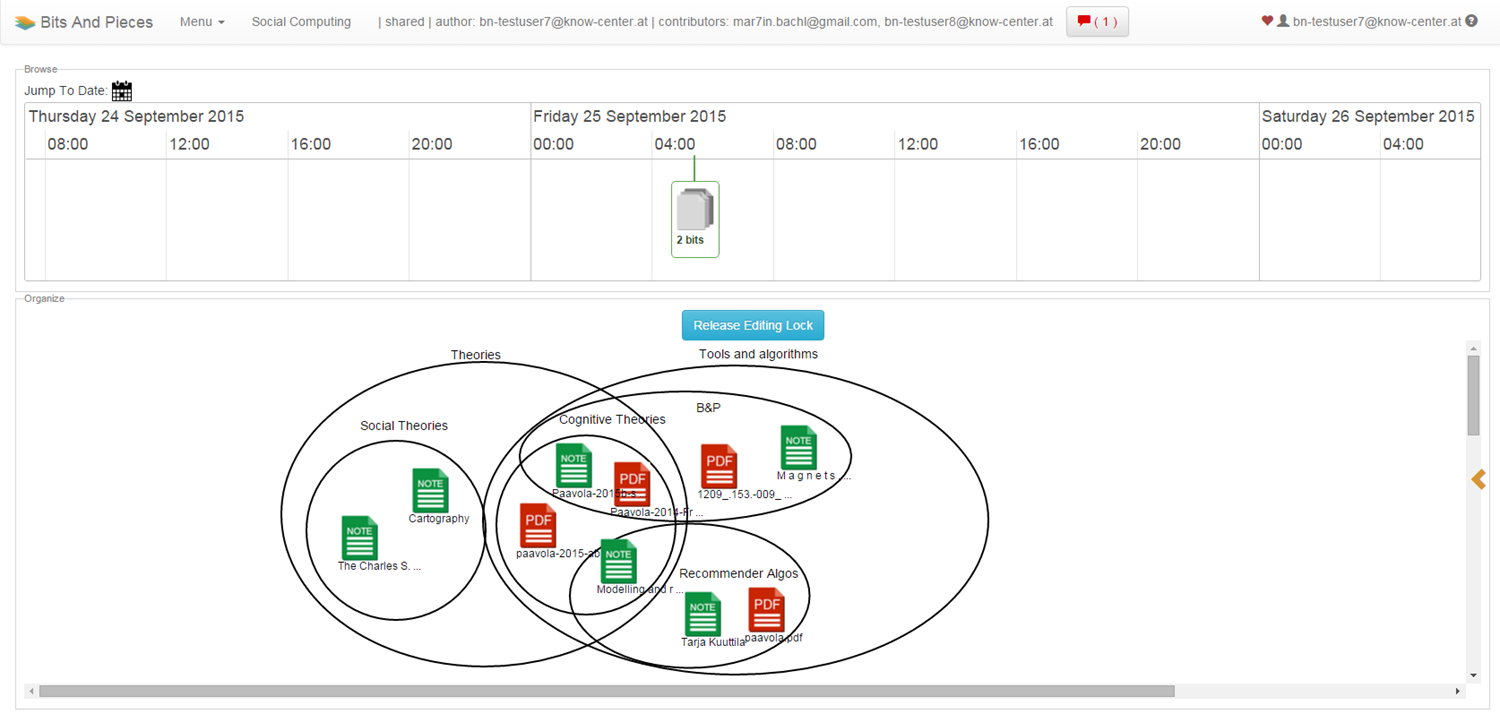

The achieved design of this DBR effort is the “Bits and Pieces” (B&P) tool (see Figure 1 and this video), but the results include the identification of necessary affordances being applicable to many other tools (such as Confer). In this report examples of these affordances are given within B&P (see Section “Findings”) and connected third party tools (e.g., Evernote).

Please, see [2] [3] [4] [5] for more details on the iterations and the method for a summary of our approach.

Research Challenges

Professionals, such as healthcare professionals, come across many different experiences and learning triggers during their work: i.e. there is a wealth of informal learning experiences popping up every working day (Contextual Inquiry; [6]). Reflecting about those experiences is important in professional practice [7].

However, time constraints prevent professionals from directly reflecting on experiences during busy working time, and patterns and connections between experiences are often not spotted (Contextual Inquiry, Iteration 1 & 6). This limits how they can be understood and used in practice. Experiences are often only recorded on quickly scribbled notes (paper or digital) if they are captured at all (Contextual Inquiry; Iteration 1, 2 & 6). This unsystematic recording of informal learning experiences over a broad collection of tools and methods leads to forgetting the location of the bits and pieces of information or simply losing them (Iteration 1 & 6). Forgetting or losing track of those experiences means missing a great opportunity for individual self-development in terms of continuous professional development (CPD; see General Medical Council), which is required in the annual appraisal of all staff and the five yearly revalidation of doctors (Contextual Inquiry; [8]).

During more flexible working times, the recorded experiences should be centrally accessible to ease the remembering and elaboration of experiences (Iteration 1, 3, 5, 6 & 7). But even if the experiences are stored in one place, professionals need support to recall them. Therefore, professionals need meaningful cues that are related to their original memory traces to remember the respective experiences (Iteration 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, & 7). Once the experiences are recalled, experiences need to be related to each other and to prior knowledge to discover patterns and achieve meaningful learning (Iteration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 & 9). Without the right support, daily stress can compromise the elaboration, meaning potential benefits for the individual and the company remain unexploited (Iteration 1).

In the company context, it is useful to share these elaboration outcomes with others (with different job roles and expertise), who work together and whose work will interact at times (e.g., shared care of patients, joint work on developing new protocols, understanding new guidelines) (Iteration 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 & 9). Their work requires them to act together, and sometimes across practices (organisations) (Iteration 4, 5, 6, 7 & 9). Many emails are sent and misunderstandings take a long time to be solved: i.e., sometimes people talk about the same things but use different words (Iteration 6, 7 & 9).

Theoretical Background

Informal learning is episodic in nature, meaning that episodes of learning experiences are distributed over working time [9]. Hence, informal learning experiences are multi-episodic and happen on a just in time basis [10]. There is a wealth of these informal learning experiences ranging from picking up a suggested reading during a short chat with a colleague, to profound ones connected to a certain professional activity. All of them are legitimate and contribute to informal learning. These experiences are memorized in episodic memory traces and can, therefore, be recalled based on time based cues [9]. If there is enough time during collection, an interaction of the episodic and semantic memory traces might take place that enables remembering informal learning experiences based on semantic cues as well [11].

Making sense of traced informal learning experiences then involves a process of mental categorization, which happens in “semantic memory”. From the perspective of Human Computer Interaction (HCI), sensemaking has been defined as “the process of encoding retrieved [external] information to answer task-specific questions” [12]. Sensemaking consists of the reciprocal interchange of bottom-up and top-down sub processes, which either generate new representations or instantiate existing representations upon the information at hand to gradually fit them to the underlying data. In particular, there are two meta-loops interacting during the process generation and instantiation of representations [13]: an information foraging loop for browsing and narrowing down the data and an organizing loop (also coined sensemaking loop) for introducing new concepts and producing final representations.

Meaning making (collaborative sensemaking) appears in the interactions of people with or within all kinds of artefacts (e.g., documents, pictures & chats; [14]: i.e., it “takes place when multiple participants contribute to a composition of interrelated interpretations”. Interpretations can thereby take the form of predications, commentary, restatements, or expressions and can be expressed in acts such as the creation and modification of ideational entities. In other words, meaning making takes place when multiple collaborators contribute to a composition of interrelated manipulations of digital artefacts. These meaning making efforts lead to the establishment of a shared understanding within the minds of the involved collaborators that enables them to collaboratively solve problems and arrive at an agreed solution [15] [16].

Method

The investigation of this design problem has been conducted in a four year design-based research study. We started contextual inquiry to set the scene and gain an initial understanding of the domain. This allowed us to identify initial research challenges in form of design problems and conceive a first design idea to be investigated. Afterwards, the DBR study focused on the parallel and iterative development of the understanding of the domain, the theoretical grounding and the design (see Figure 2; a DBR project can contribute to a fourth research area (i.e., methodology), which was not addressed in the underlying study) to come up with a technological support for informal workplace learning addressing the research challenge (see Section “Research Challenges”).

For each of those three research areas, in each iteration, we set up research questions triggered by a design problem of the domain, inferred hypotheses from theory, designed a prototype and evaluated it using an appropriate study design and methods for analysis. For example, In iteration two, we used paper prototyping (see Video 1) to come up with a low-fidelity prototype for co-designing with our healthcare professionals.

Pictures of paper prototyping results as well as interviews were subsequently analysed with qualitative content analysis to answer the hypotheses and explore the research areas. Thereby, the focus was put on the analysis of the usage, or more specifically the appropriation of affordances [2]. It allowed us to put the professional practice in the center of our interest and, hence, ensure the tool is professionally relevant and usage is likely to be continued. For this purpose, affordances have been studied in terms of their effectiveness by observing their appropriation by professionals in the field. Besides the named methods, we relied upon questionnaires, group interviews, association tests and log file analysis among others to address the stated hypotheses in an appropriate manner.

In this way, nine different design iterations have been pursued narrowing down the design freedom and concretizing the design artefact to reach the current design (see Figure 3). The iterations included one conceptual prototyping, two paper prototyping, one first functional software prototyping and five later software prototyping phases in the field. The ninth iteration represented a one-day guided usage workshop which allowed the professionals to experience collaboration and to enable feedback on the perceived impact.

Findings

In the following section the main findings of the four year design work will be presented in an aggregated form with the respective affordances that are required for meaningful tool support.

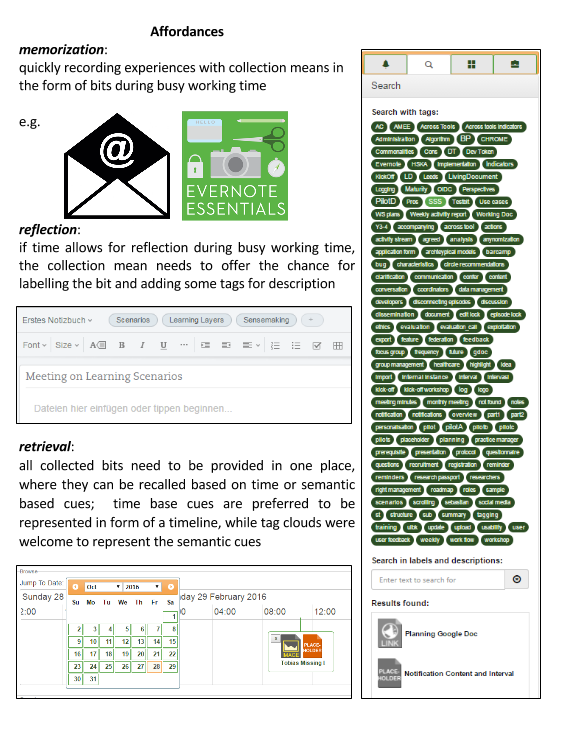

In informal learning, self-driven and self-made experiences represent the “data” in sense- and meaning making. Therefore, the cognitive mechanisms of memorization (Iteration 1, 2 & 3), reflection (Iteration 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 & 8) & retrieval (Iteration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 & 8) seem to play an important role in sensemaking of informal learning experiences. Therefore, there is the need to provide affordances to address these cognitive mechanisms:

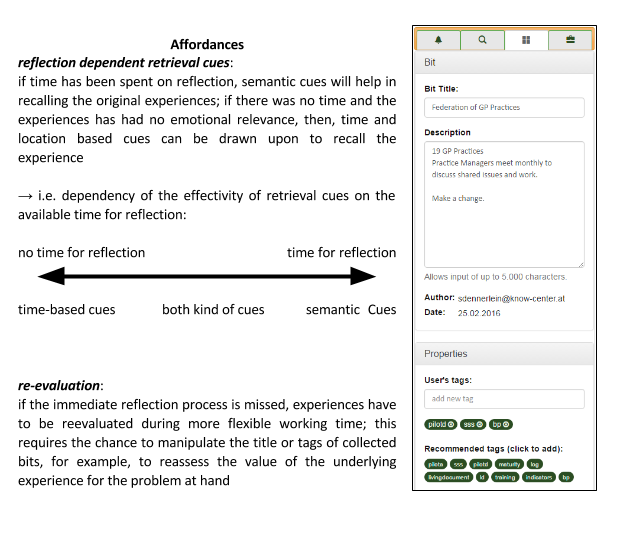

The time spent on reflection while recording an experience as well as the emotional relevance determine successful retrieval cues for respective memory traces and, hence, the success of recalling an experience (Iteration 3, 4, 5, 6 & 7).

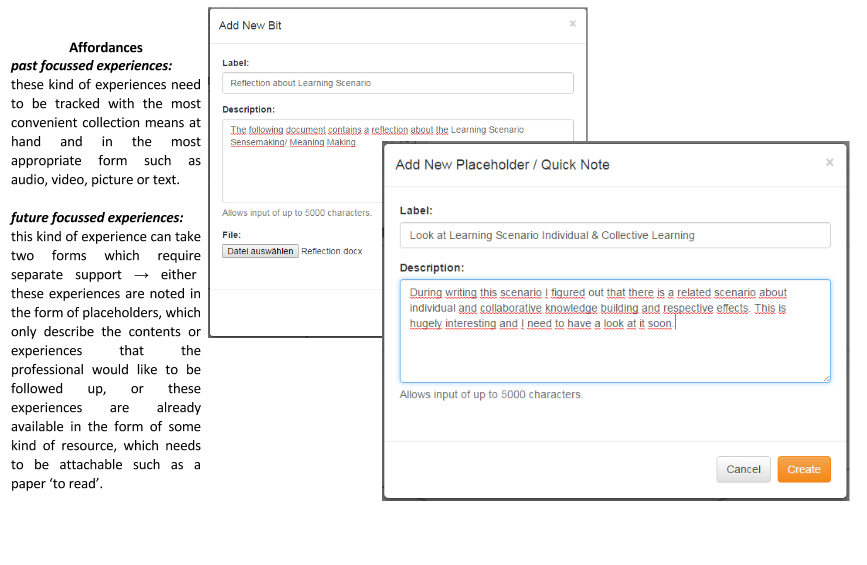

With respect to the recorded informal learning experiences, past and future focused experiences need to be differentiated (Iteration 1, 2, 3 & 5). While past focused experiences describe self-experienced and elaborated events in terms of reactive learning, future focused experiences represent discoveries that can’t be addressed at the moment and result in to-dos or to-reads: e.g., superficial experiences such as stumbling upon and noting an interesting article while scanning a magazine that can’t be read at the moment. Often they are also inferred from the past one and describe intentions in terms of deliberate learning. Therefore, there is the need to provide affordances to address these different kinds of experiences:

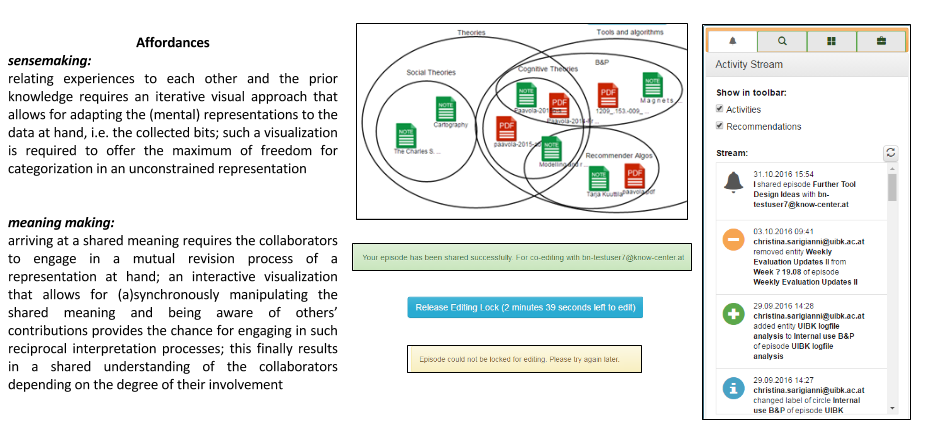

Making sense of experiences requires the narrowing down of collected bits with respect to a certain topic, issue or challenge. Based on a meaningfully related subset of bits, experiences can then be related to each other, individually or collaboratively, to make sense of them (Iteration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 & 9). This elaboration and connection of the experiences to prior knowledge facilitates the application of respective knowledge in everyday practice and improves team work based on increased shared understanding (see here; Iteration 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Therefore, there is the need to provide affordances to address these sense and meaning making efforts:

Sharing and co-creation in sensemaking represent social processes that are not only welcome, but expected from professionals. Especially, the collaborative part of the social processes seems to result in the following benefits and effects on practice (Iteration 9): 1) Online Benefits - Mutual revision process or collaboration helps professionals to understand other’s roles and experiences, expand their own understanding and trigger new ideas of how to go on. Besides, there are less or lowered barriers to raise something: i.e. online collaboration provides a voice for others who are less likely to speak up during a f2f meeting and give their opinion. 2) Offline Benefits - When prepared right, collaboration is time saving (i.e. it takes effort, but can lead to more efficient problem solving, for example) and leads to positive impact on offline f2f collaboration such as better understanding of the capabilities and knowledge of colleagues, more effective distribution of work and more efficient offline meetings as well as more meaningful discussion.

Summary

| Sensemaking | Meaning Making | |

| Description | Individual elaboration of self recorded experiences with respect to a certain topic or problem by semantically categorizing them. | Collaborative collection and elaboration of experiences with respect to a certain topic or problem. |

| Motivation | Wealth of informal learning experiences Danger of forgetting experiences or losing track of notes (which could be saved in different places - several box files, notebooks and clouds) Missing elaboration of limits chances of individual self development for applying knowledge in practice | Chance of effective teamwork Mean to achieving a shared vocabulary enabling deeper collaboration Need for acquiring a shared understanding about a collective goal and the way to approach it |

| Tool functionalities Intended affordances | Usage of the timeline to recall experiences based on time based cues or the tag cloud for semantic cues. A Venn diagram based visualization allowing the clustering of experiences in overlapping circles indicating shared structures. | Asynchronous collaborative usage of the Venn Diagram based visualization for the elaboration of the joint experiences regarding a certain topic or problem. Awareness functionalities such as activity stream and communication features such as a discussion feature allow for an understanding of the evolution of the joint ideas and precise interpretation of the mutual contributions. |

| Benefits | Longer lasting and applicable knowledge extracted from the contextualized informal learning experiences faced during work. Results of sensemaking processes can be extracted and used for appraisal and revalidation. | Traceable (e.g. Activity Stream and the Activity Reports via Mail) and understandable collaboration results that allow for tracking how a certain meaning was achieved. Involvement in the collaboration process helps participants achieve shared understanding and thus improves future online and offline collaboration. |

Further Readings

Contributing Authors

Sebastian Dennerlein, Tobias Ley, Tamsin Treasure-Jones, Dominik Kowald, Elisabeth Lex

References

- T. Ley, J. Cook, S. Dennerlein, M. Kravcik, C. Kunzmann, K. Pata, J. Purma, J. Sandars, P. Santos, A. Schmidt, M. Al-Smadi, and C. Trattner, “Scaling informal learning at the workplace: A model and four designs from a large-scale design-based research effort,” British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 1036–1048, Sep. 2014. DOI: 10.1111/bjet.12197

- S. Dennerlein, V. Tomberg, T. Treasure-Jones, D. Theiler, E. Lex, S. Lindstaedt, and T. Ley, “The Role of Memory and Sensemaking in Healthcare Professionals’ Informal Learning at Work: A Design-Based Research Study,” uner review, 2018.

- S. Dennerlein, T. Treasure-Jones, E. Lex, and T. Ley, “The role of collaboration and shared understanding in interprofessional teamwork,” in International Conference of Medical Education (AMEE2016), 2016.

- S. Dennerlein, M. Rella, V. Tomberg, D. Theiler, T. Treasure-Jones, M. Kerr, T. Ley, M. Al-Smadi, and C. Trattner, “Making sense of bits and pieces: A sensemaking tool for informal workplace learning,” in European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, 2014, pp. 391–397. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-11200-8_31

- V. Tomberg, M. Al-Smadi, T. Treasure-Jones, and T. Ley, “A Sensemaking Interface for Doctors’ Learning at Work: A Co-Design Study Using a Paper Prototype,” in ECTEL meets ECSCW 2013: Workshop on Collaborative Technologies for Working and Learning, 2013, p. 54.

- G. Fitzpatrick and G. Ellingsen, “A review of 25 years of CSCW research in healthcare: contributions, challenges and future agendas,” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), vol. 22, no. 4-6, pp. 609–665, 2013.

- D. A. Schön, The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action, vol. 5126. Basic books, 1983.

- K. Shaw, L. MacKillop, and M. Armitage, “Revalidation, appraisal and clinical governance,” Clinical Governance: an international journal, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 170–177, 2007.

- M. Eraut*, “Informal learning in the workplace,” Studies in continuing education, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 247–273, 2004.

- J. Kooken, T. Ley, and R. De Hoog, “How do people learn at the workplace? investigating four workplace learning assumptions,” in European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, 2007, pp. 158–171.

- P. Hemmer and M. Steyvers, “Integrating episodic and semantic information in memory for natural scenes,” in Proceedings of the 31th annual conference of the cognitive science society, 2009, pp. 1557–1562.

- D. M. Russell, M. J. Stefik, P. Pirolli, and S. K. Card, “The cost structure of sensemaking,” in Proceedings of the INTERACT’93 and CHI’93 conference on Human factors in computing systems, 1993, pp. 269–276.

- P. Pirolli and S. Card, “The sensemaking process and leverage points for analyst technology as identified through cognitive task analysis,” in Proceedings of international conference on intelligence analysis, 2005, vol. 5, pp. 2–4.

- D. D. Suthers, “Collaborative knowledge construction through shared representations,” in Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2005, pp. 5a–5a.

- S. Mohammed and B. C. Dumville, “Team mental models in a team knowledge framework: Expanding theory and measurement across disciplinary boundaries,” Journal of organizational Behavior, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 89–106, 2001.

- S. A. Converse and S. E. Kahler, “Knowledge acquisition and the measurement of shared mental models,” Unpublished manuscript, Naval Training Systems Center, Orlando, FL, 1992.