Progressive Inquiry & Knowledge Building (HC)

Highlights

-

An adaptation of the Progressive Inquiry model [1] has been successfully applied as a scaffolding mechanism to support informal learning, and in particular, collaborative discussion and knowledge building of workgroups at the workplace.

-

Confer has been developed according to a co-design approach with Healthcare professionals with the main aim of providing support to groups of professionals (General Practices in the Healthcare context) working collaboratively on a task or project.

-

LAYERS Evaluation results show how Confer, and our adaptation of the Progressive Inquiry model, is especially useful to facilitate, capture knowledge and provide structure and guidance to the workgroup discussions especially during face to face meetings. But also asynchronously when a wider group has to be involved.

Practical case/ Example / Scenario

Providing support to bridge between face to face and online discussions by workgroups is needed based on our research with General Practices in the North of England, UK (see: [2], [3], [4]). For instance, national clinical guidelines have to be understood, interpreted and implemented according to local needs; this is why it is common for workgroups to be set-up (either within a General Practice or across Practices) to review new guidelines and come up with proposals for local implementation. One typical scenario sees Practice Managers from different General practices meeting monthly to discuss shared issues and work (these federations of Practice Managers tend to be geographically organised i.e. federations have tended to form within a recognised regional location).

This is just one example of the many work-based problems or projects that could prompt the setting up of a workgroup and it is within these contexts that ‘informal learning’ takes place. Key issues identified are: to ensure that the exchange of knowledge is not lost, plus keeping the work focused and flowing.

Research problem

The social aspect of learning for this scenario is critical, so in order to understand this one of the main theories considered has been the ‘Cultural Historical’ theory where social dimension is paramount in the formation of the mind (Post-Vygostkian theories). In particular, one of the main research questions to be explored was raised by [5]: to what extent can cognition be considered situated in particular contexts and distributed across individuals acting in those settings?

Therefore, through the exploration of this learning scenario (and particularly with the application of Confer) we want to observe if the learning actions of individuals are influenced (or not) by the actions of the group, and by the particular context where the actions take place. A list of more specific research questions and the corresponding results can be found in the Findings section.

Theoretical Contribution

One of the strengths of our design approach is that we do not commit to a single theoretical tradition. Rather, in true design science spirit, this learning scenario draws on multiple theories: post-Vygotskian concept of hybridity in professional learning networks [5], knowledge building communities [6] and the related concept of progressive inquiry [1], plus emerging concepts like social machines [7].

For this particular learning scenario, Knowledge building is in essence a “coherent effort to initiate students (in this case our HC professionals) into knowledge creating culture” [8]. It is about embedding pedagogic design in the context for which it is destined to be implemented and is thus distinct from connectionist or behaviourist approaches. “Support Knowledge Building Discourse” has been considered as one of the main meta-design principles [9] to give support to this learning scenario in the Healthcare context.

Therefore, giving support to discussion and negotiations in professional workgroups when doing a task in a specific context was identified as a need. In order to support this need and ‘embedding pedagogic design in the context’, an adaptation of the original Progressive Inquiry (PI) model proposed by [1] was defined after some co-design sessions with HC professionals who work in general practices. The following storyboards captures the main learning tasks discussed during co-design sessions with HC professionals to support this Learning Scenario:

-

Storyboard Working Group Tools: working groups collaborate asynchronously online. Link: https://goo.gl/Xwu0lE

-

Storyboard Discussion Working Group: Workgroup - dealing with issues. Link: https://goo.gl/BseZKB

The Storyboards were useful to confirm with the HC professionals how to support the process of collaborative discussion. One the one hand, the storyboard ‘Working group tools’ confirmed the need to support collaborative discussions during f2f meetings but also asynchronously at the distance. The participants also agreed that something necessary after finishing the discussion was the obtention of a final report containing the knowledge build by the group. On the other hand, the ‘Discussion working group’ storyboard contained an illustration of how to mediate the collaborative discussion through our adaptation of the PI Model, again the participants agreed that integrating this structured process in a tool would be a good idea to support their discussion.

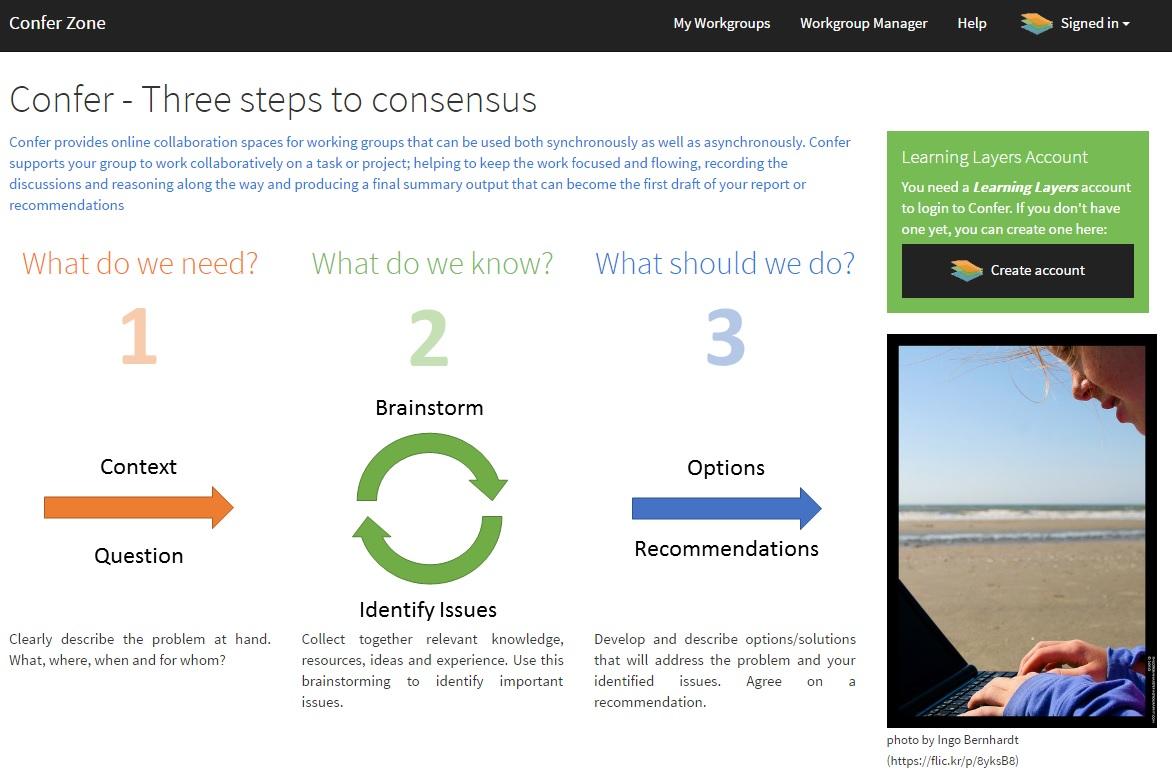

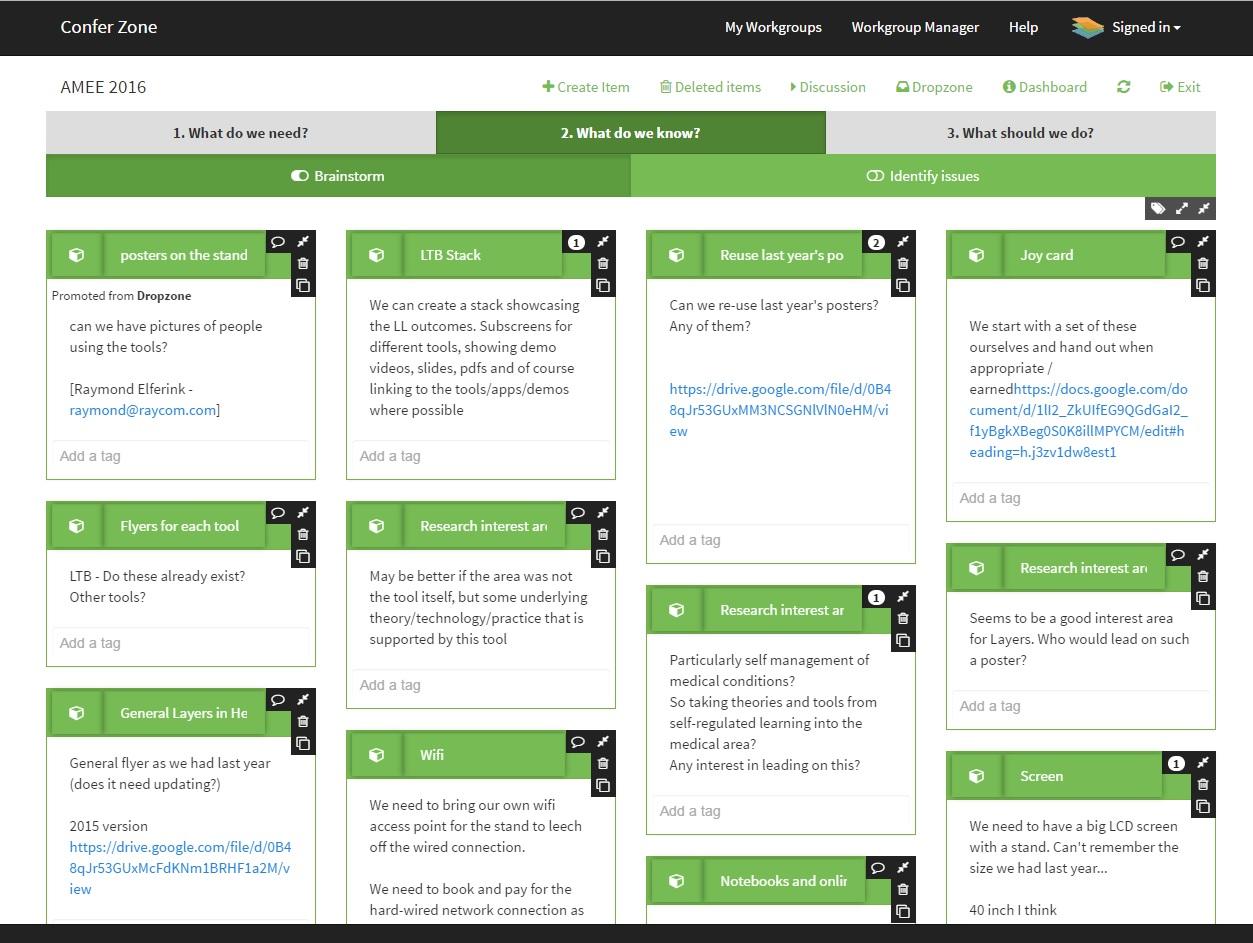

By taking into account these feedback from the co-design sessions, Confer was built as a Learning Layers tool to support knowledge building in a process of collaborative discussion (more details about the design process here: [10]. The successive elements of progressive inquiry (used to support work groups) are originally described in [11]. Originally, the PI model was proposed to describe process of discussion around a table. We follow the interpretation of the PI model proposed by [11] but adapting it to the needs of our end-users (professionals in the Healthcare domain). The model is used to scaffold and guide the workgroup members during their collaboration discussion and co-creation tasks. In each task (creating the context; setting up research questions; brainstorming; identifying issues; collecting options and making final recommendations) Confer provides features to engage the process of discussion and the egalitarian collection of shared learning data. Figures 3 shows the welcome page of Confer which describes our adaptation of the PI model. Figure 4 shows an screenshot of the Brainstorm section where different knowledge ideas have been collected by a workgroup.

Welcome interface of Confer describing our adaptation of the PI model

What do we know? Brainstorm section to support knowledge building

Design Patterns

During Year 3 and according to the Layers Co-design and Participatory Patterns Design methodologies, we articulated a set of design principles and patterns which were used to guide the software development of Confer. As a result we obtained five patterns (the long description of these patterns can be found in D2.3 pp. 36 - 42 here). The evaluation done in the HC workplace during Y4 has been used to corroborate these patterns, more detail can be found in the Evaluation Report of the Healthcare sector (section 3.2) [Link: M-12] where we have included 1) a description of the expected contribution of each pattern and 2) the findings obtained from the Year 4 evaluation that we used to corroborate these patterns.

Methods/Evidence

-

Co-design interventions during years 1,2 and 3. See Co-Design Framework

-

Y1 and Y2 empirical analysis in the HC (see: [2] , [3], [4] ).

-

Participatory Patterns Workshop (see the Confer Participatory Patterns Workshop) [10].

-

Evaluation of LAYERS tools in Healthcare (Pilots A, B, C) during year 4.

Findings

The following findings provide evidence of how Confer was effective and played an important role in supporting progressive inquiry and knowledge building processes in workplace contexts. The goal of Year 4 was to perform a summative evaluation of the Layers tools associated with real work settings in the healthcare sector. Therefore, healthcare professionals had the chance to use Confer for a period of time and provide feedback on their experiences. The first context of study concerns GP practices working together in a federation and involves pilot group A, and the second context concerns distributed teams with a focus on training/education and involves pilot groups B and C. More detail can be found in the Evaluation Report of the Healthcare sector [Link: M-12].

As we have indicated in the Research problem section our main research question is: To what extent can cognition be considered situated in particular contexts and distributed across individuals acting in those settings? This question has been adapted to three sub-research questions that considers the use of Confer in real contexts (groups of HC professionals) to support their knowledge building during collaborative discussions processes:

-

RQ1: Is the adaptation of our PI model a good scaffolding mechanism that provides structure and guidance during Knowledge building processes?

-

RQ2: Which groups of professionals would benefit most from using Confer and for which tasks and in which contexts?

-

RQ3: We think that an early exposure to and collaboration on ideas will enhance the feeling of workgroup engagement. Would this also means that new proposals/processes developed using Confer are more likely to be adopted?

And as follows we summarize the derived findings:

In regards to RQ1 we have confirmed how the PI model integrated by Confer helps to develop a more structured approach on their discussion. This structure gave a sense of formality to the group and allowed the members to align their ways of contributing to the discussion. The following quotes from Pilot B confirms this statement:

Prior to the HC qualitative study it was unexpected from our hypothesis that the main benefit of Confer would be to use the tool to support the process of collaborative discussion during f2f meetings. Confer can mediate the discussion in real time by showing the different ideas discussed during the meeting organized in a specific structure. As a consequence, the ideas are collected and organized in Confer and others members of the workgroup (who did not have the opportunity to join the f2f meeting) can have access to the content and potentially enhancing the feeling of being more connected with the group. So these findings can be used to answer our RQ2. We can conclude that groups of professionals that have very tight agendas and need to use the time of f2f meetings very efficiently to get conclusions are one of the main target groups of Confer. Also workgroup members that need to share ideas with a wider group from time to time, and incorporate the ideas of the wider group into the discussion (by using the Dropzone feature - more detail in the next finding description). The following quotes support these findings:

The Dropzone is a section of Confer where external users can send ideas by using a confer email address associated to each workgroup (see more detail here) By allowing the wider group to email in ideas and links to the Dropzone it provides them with an easy way of having an early influence on the tasks of the working group. Our hope was that the workgroup members will therefore feel more engaged with the work and be more willing to accept the recommendations that arise (see RQ3). The feedback and observations collected from Pilot C shows how the team used Confer to share their ideas (and their idea development process) at a much earlier stage with the wider group, and then to gather input into these early ideas from the group both through Confer itself and at meetings.

Reflections

-

Face to face meetings play a very important role in learning scenarios contexts where professionals are normally distributed in different locations and with very different time schedules. This context has some inherent challenges around staying on-topic; capturing discussions; being more structured and effective; keeping momentum going between meetings; as well as keeping those who miss the face to face encounters more connected.

-

Due to the time constraints of f2f meetings, participants want to use the meetings to efficiently complete specific steps, and get conclusions from the meeting and/or to check very specific contributions made in between different f2f meetings.

-

The findings show how the adaptation of the PI model applied in Confer as a scaffolding mechanism provides guidance and help professionals to structure their knowledge building especially when they collaborate face to face in meetings; But also having a facility as the Dropzone (the Dropzone is a section of Confere where external users can send ideas by using a confer email address associated to each workgroup) is useful to collect knowledge from external members who cannot join the meeting.

-

In keeping with the spirit of our interactive and collaborative approach, several potential uses of Confer were identified by our pilot participants. One example was provided by members from Pilot C (HC professionals with a focus on training/Education) sparked new ideas for how to use the tool Confer itself to support the group “one of the guys also had a new novel idea [support for mentoring] for how we could use Confer which he thought it would be very useful in his organisation” [PilotC-FinalWorkshop]. So a future application in terms of using Confer as a tool to work could be to support processes of mentoring. A member of this pilot commented that he could get people to kind of use Confer and he would then come in and view the contributions from the outside and be able to give them feedback, without having to kind of meet personally with people.

Links:

Other places of the website where the scenario has been used/developed/supported

-

Tools connected to the scenario: www.confer.zone, and see tool description.

-

Cases where scenario has been implemented

-

Methods through which scenario was created:

Contributing Authors:

Patricia Santos (UWE), John Cook (UWE), Tamsin Treasure-Jones (Leeds), Micky Kerr (Leeds), Raymond Elferink (Raycom), Yishay Mor

References:

- H. Muukkonen, K. Hakkarainen, and M. Lakkala, “Collaborative technology for facilitating progressive inquiry: Future learning environment tools,” in Proceedings of the 1999 conference on Computer support for collaborative learning, 1999, p. 51.

- P. Santos, J. Cook, T. Treasure-Jones, M. Kerr, and J. Colley, “Networked scaffolding: Seeking support in workplace learning contexts,” in Networked Learning Conference, 2014.

- P. Santos, S. Dennerlein, D. Theiler, J. Cook, T. Treasure-Jones, D. Holley, M. Kerr, G. Attwell, D. Kowald, and E. Lex, “Going beyond your Personal Learning Network, using Recommendations and Trust through a Multimedia Question-Answering Service for Decision-support: a Case Study in the Healthcare.,” Journal of Universal Computer Science, 2016.

- D. Holley, P. Santos, J. Cook, and M. Kerr, “‘Cascades, torrents & drowning’ in information: seeking help in the contemporary general practitioner practice in the UK,” Interactive Learning Environments, pp. 1–14, 2016.

- H. Daniels, Vygotsky and research. Routledge, 2008.

- M. Scardamalia and C. Bereiter, “Knowledge building environments: Extending the limits of the possible in education and knowledge work,” Encyclopedia of distributed learning, pp. 269–272, 2003.

- N. R. Shadbolt, D. A. Smith, E. Simperl, M. Van Kleek, Y. Yang, and W. Hall, “Towards a classification framework for social machines,” in Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web, 2013, pp. 905–912.

- M. Scardamalia and C. Bereiter, “Knowledge building,” The Cambridge, 2006.

- J. Cook, T. Ley, R. Maier, Y. Mor, P. Santos, E. Lex, S. Dennerlein, C. Trattner, and D. Holley, “Using the hybrid social learning network to explore concepts, practices, designs and smart services for networked professional learning,” in State-of-the-Art and Future Directions of Smart Learning, Springer, 2016, pp. 123–129.

- Y. Mor, J. Cook, P. Santos, T. Treasure-Jones, R. Elferink, D. Holley, and J. Griffin, “Patterns of practice and design: Towards an agile methodology for educational design research,” in Design for Teaching and Learning in a Networked World, Springer, 2015, pp. 605–608.

- M. F. De Laat and P. R. J. Simons, “Collective learning: Theoretical perspectives and ways to support networked learning,” European Journal for Vocational Training, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 13–24, 2002.